History of The Brooklyn Nine

The History of The Brooklyn Nine: Inning by Inning

First Inning : Play Ball

Between 1840 and 1859, more than four million people immigrated to America. Thirty-two percent (like my own family, who came later) were German, and an amazing three out of every four of the new immigrants landed in Manhattan. In 1854 alone, more than 300,000 immigrants came to New York–more than the entire population of the city just fifteen years prior.

Two massive fires swept through lower Manhattan in this era, the first in 1835 and another in 1845. In the first, the flames consumed 674 buildings before they could be contained, doing an estimated 18 to 26 million dollars worth of damage. Only two people died, however, as the southern tip of Manhattan island was by this time already a purely commercial district. The 1845 fire was equally disastrous, wiping out everything from the East River west to Broad Street and north to Wall Street.

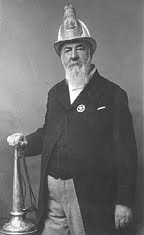

Alexander Cartwright, considered by many today to be the father of modern baseball, was indeed a fireman, and his Knickerbocker Volunteer Fire Department gave its name to the baseball club Cartwright helped found. Taking their cue from rules being used by many less organized baseball games like “town ball,” “three-out, all-out,” and “one old cat,” the Knickerbockers were the first to write down rules that established a standard distance between the bases, introduced foul territory, and, most importantly, ended the practice of throwing the ball at runners (“soaking” them) to get them out.

Alexander Cartwright, considered by many today to be the father of modern baseball, was indeed a fireman, and his Knickerbocker Volunteer Fire Department gave its name to the baseball club Cartwright helped found. Taking their cue from rules being used by many less organized baseball games like “town ball,” “three-out, all-out,” and “one old cat,” the Knickerbockers were the first to write down rules that established a standard distance between the bases, introduced foul territory, and, most importantly, ended the practice of throwing the ball at runners (“soaking” them) to get them out.

And Cartwright did indeed leave New York to seek his fortunes in California, eventually going all the way to Hawaii. He introduced the Knickerbocker baseball rules to towns and players all along the way, becoming a sort of Johnny Appleseed of America’s game.

19th Century baseball reproductions

Rules and Regulations of the Knickerbocker Baseball Club – 1845

Second Inning : The Red-Legged Devil

By the time of the American Civil War, baseball had grown by leaps and bounds. Previously only an amateur game, players on teams like Brooklyn’s Excelsiors, Atlantics, andEckfords were beginning to be lured away by money to play for other teams, and some teams began putting up fences around their fields and charging admission. “Purists” complained, but professional baseball was here to stay. There were significant changes to the game in this era too: balls could no longer be caught on the bounce for an out, the stolen base was introduced, and pitchers, though still throwing underhand, were adding fancy pitches like curveballs to their arsenals. The New York Game, based on rules that evolved from the Knickerbocker rules, soon came to be the dominant form of baseball played throughout America, especially as Yankees took their game with them as they marched through the South in the War Between the States.

By the time of the American Civil War, baseball had grown by leaps and bounds. Previously only an amateur game, players on teams like Brooklyn’s Excelsiors, Atlantics, andEckfords were beginning to be lured away by money to play for other teams, and some teams began putting up fences around their fields and charging admission. “Purists” complained, but professional baseball was here to stay. There were significant changes to the game in this era too: balls could no longer be caught on the bounce for an out, the stolen base was introduced, and pitchers, though still throwing underhand, were adding fancy pitches like curveballs to their arsenals. The New York Game, based on rules that evolved from the Knickerbocker rules, soon came to be the dominant form of baseball played throughout America, especially as Yankees took their game with them as they marched through the South in the War Between the States.

Contrary to popular belief, Abner Doubleday, who makes an appearance this inning as a Union General, did not invent the game of baseball in a cow pasture in Cooperstown, New York. That myth was most likely started by sports star turned sporting goods manufacturer Albert G. Spalding, who was desperate to convince the world that baseball had been a truly American invention with no ties to older games or other countries. Despite zero evidence that Doubleday had ever even seen a baseball, much less invented the game, the idea was presented as fact, a Hall of Fame was built in Cooperstown, and the myth persists to this day. Doubleday was though the commanding officer of many Union regiments, including the “Red-Legged Devils” of the Brooklyn Fourteenth, who continued to wear their peculiar pants long after the Union issued standard blue uniforms to the rest of the army.

Contrary to popular belief, Abner Doubleday, who makes an appearance this inning as a Union General, did not invent the game of baseball in a cow pasture in Cooperstown, New York. That myth was most likely started by sports star turned sporting goods manufacturer Albert G. Spalding, who was desperate to convince the world that baseball had been a truly American invention with no ties to older games or other countries. Despite zero evidence that Doubleday had ever even seen a baseball, much less invented the game, the idea was presented as fact, a Hall of Fame was built in Cooperstown, and the myth persists to this day. Doubleday was though the commanding officer of many Union regiments, including the “Red-Legged Devils” of the Brooklyn Fourteenth, who continued to wear their peculiar pants long after the Union issued standard blue uniforms to the rest of the army.

My own family’s American journey began in 1861, when 19-year-old Louis Alexander Gratz, a German Jew, landed in New York City with ten dollars in his pockets and no knowledge of English. A few months later he heeded President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to fight in the Civil War, and less than a year after arriving in America Louis Gratz was an officer in the Union Army. He fought his way south into Kentucky and Tennessee, reaching the rank of major and commanding a regiment in the Battle of Chickamauga. When the war ended, Louis found himself in Knoxville, Tennessee (my hometown!), where he earned a law degree, married into a prominent local family, and eventually became the first mayor of North Knoxville. I named the main character in “The Red-Legged Devil” Louis in honor of Louis Alexander Gratz.

My own family’s American journey began in 1861, when 19-year-old Louis Alexander Gratz, a German Jew, landed in New York City with ten dollars in his pockets and no knowledge of English. A few months later he heeded President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to fight in the Civil War, and less than a year after arriving in America Louis Gratz was an officer in the Union Army. He fought his way south into Kentucky and Tennessee, reaching the rank of major and commanding a regiment in the Battle of Chickamauga. When the war ended, Louis found himself in Knoxville, Tennessee (my hometown!), where he earned a law degree, married into a prominent local family, and eventually became the first mayor of North Knoxville. I named the main character in “The Red-Legged Devil” Louis in honor of Louis Alexander Gratz.

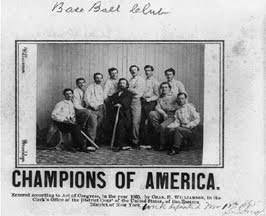

Brooklyn in the Civil War: Brooklyn 14th, Company G

Brooklyn in the Civil War: Brooklyn 14th Reenactors

Brooklyn in the Civil War: Union Prisoners Play Ball

Third Inning : A Ballad of the Republic

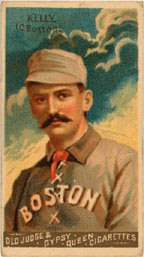

As professional baseball became the National Pastime, Mike “King” Kellybecame one of its first great stars. A key player for the powerful Chicago White Stockings teams of the 1880s, Kelly led the league in runs, stolen bases, and batting average for several years. Kelly was widely known (and loved) for his antics on and off the field, which did in fact include traveling with a Japanese manservant and a pet monkey. White Stockings first baseman and manager Cap Anson was never a fan though, and in 1887 Kelly was sold to the Boston Beaneaters for the then unheard-of sum of $10,000.

As professional baseball became the National Pastime, Mike “King” Kellybecame one of its first great stars. A key player for the powerful Chicago White Stockings teams of the 1880s, Kelly led the league in runs, stolen bases, and batting average for several years. Kelly was widely known (and loved) for his antics on and off the field, which did in fact include traveling with a Japanese manservant and a pet monkey. White Stockings first baseman and manager Cap Anson was never a fan though, and in 1887 Kelly was sold to the Boston Beaneaters for the then unheard-of sum of $10,000.

A true showman, Kelly is credited with being the first ballplayer to give autographs, and the first to sell the rights to his name and image for product advertisement. The song “Slide, Kelly, Slide” became a nationwide hit when it was released on a phonograph cylinder by Edison Studios, and after his playing career Kelly traded in on his fame to star on the vaudeville stage. In many ways though, Kelly’s story is as sad as that of the slugger in “Casey at the Bat.” Heavy drinking cut short Kelly’s playing career and his life. Already washed out of professional baseball, Kelly died when he was just 36 years old.

Kelly’s era saw more changes in baseball, including overhand pitching, foul balls counted as strikes, and the widespread introduction of fielding gloves to the game. Big changes were in store for Brooklyn around this time too. The Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883, and in 1894 Brooklyn, until then an independent city, voted (just barely!) to join Manhattan, The Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island as one of the five boroughs of New York City.

The title of this story comes from the subtitle of Ernest Thayer‘s “Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic,” which was published in the San Francisco Examiner in 1888. Thayer was paid five dollars for his poem.

Mike “King” Kelly – Hall of Fame Page

Fourth Inning: The Way Things Are Now

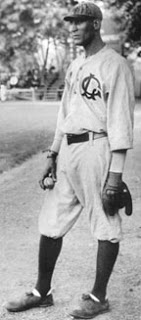

Hall of Famer Cyclone Joe Williams (later known as Smokey Joe Williams) was perhaps the greatest pitcher of his era, black or white, though he never played a day of Major League Baseball. Though never written down, Major League Baseball owners had what was known as a “gentleman’s agreement”not to sign black players to their teams. This institutional racism continued for almost fifty years until Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color barrier in 1947. In the meantime, black stars like Cyclone Joe were left to forge careers for themselves in the Negro Leagues, or overseas in Mexican and Cuban leagues.

Hall of Famer Cyclone Joe Williams (later known as Smokey Joe Williams) was perhaps the greatest pitcher of his era, black or white, though he never played a day of Major League Baseball. Though never written down, Major League Baseball owners had what was known as a “gentleman’s agreement”not to sign black players to their teams. This institutional racism continued for almost fifty years until Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color barrier in 1947. In the meantime, black stars like Cyclone Joe were left to forge careers for themselves in the Negro Leagues, or overseas in Mexican and Cuban leagues.

As far as I know, Joe Williams never tried to pass himself off as a Native American, though he was half Comanche Indian. Instead he plays stand-in here for a black man who really did try to pass for a Native American to make the Majors. In 1901, Baltimore Orioles manager John McGraw, who more famously went on to coach the New York Giants for thirty years, tried to sign black second baseman Charlie Grant to a Major League contract as an American Indian named Chief Tokohama. McGraw and Grant were busted before “Tokohama” could ever play a game, and baseball’s color line remained uncrossed for another 46 years.

Anti-Semitism, prejudice against Jewish people, was also strong in turn-of-the-century America. German Jews who had come to America in great waves in the 1840s-1880s had largely blended in with the rest of society, many “Americanizing” their last names and some even abandoning their religion or converting to Christianity, as my ancestor Louis Gratz did. (Louis covered his tracks so well, in fact, that my family didn’t know we had once been Jewish until more than a hundred years later when my grandfather began researching our family history.)

Anti-Semitism certainly existed in America, but not the way it would rear its ugly head in the early 1900s when millions of Russian Jews, driven from their homeland by anti-Jewish hate riots, fled to the United States-particularly to New York City. Unlike their German cousins, Russian Jews refused to conform, clinging to their Jewish religion, their traditional clothing, and their Yiddish language. The cultural backlash against these new Eastern European Jews carried over to all Jews, no matter how long they had been in America or how well-respected they were in their community.

In baseball, the “Dead Ball Era” was in full swing, marking the lowest run-scoring period in Major League history, a swoon that wouldn’t officially be broken until Babe Ruth burst onto the scene in the 1920s. The New York Giants and the Chicago Cubs were the class of the National League, with the Cubs winning back to back World Series titles in 1907 and 1908–the last World Series trophy the North Siders would take home for at least the next hundred years. The Brooklyn Superbas meanwhile were far from superb, placing seventh out of eight teams in 1908 with a 53-101 record. Throughout the history of the Brooklyn baseball franchise, they were known by a variety of names: The Atlantics, the Grays, the Bridegrooms, the Superbas, The Trolley Dodgers, the Robins, and finally just the Dodgers.

Joe Williams – National Baseball Hall of Fame Page

Everything Coney Island – The Coney Island Pages

Fifth Inning : The Numbers Game

In 1919 Congress passed the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, banning the manufacture, transport, and sale of alcohol in the United States. Thus began the Prohibition Era, giving rise to speakeasies, gin joints and blind pigs, and a new generation of American gangsters like Al Caponeand Bugsy Siegel. While federal agents made a show of fighting bootleggers and drinking, many local authorities turned a blind eye to people breaking Prohibition laws, and the Amendment was repealed in 1933.

The 1920s were also the heyday of overwritten, “purple prose” sports writing, and John Kieran was one of its most famous figures. Kieran wrote for The New York Times sports section for almost thirty years, filling his sports columns with references to Latin, law, poetry, nature, and the works of William Shakespeare. In the hours before ball games, Kieran could be found visiting museums, zoos, parks and libraries, and he had a habit of writing his articles in advance of the actual games. Later in life he put his vast knowledge to the test as a panelist on NBC’s long-running radio quiz show“Information, Please!” While I can’t say that Kieran ever really conspired to fix a numbers game, he certainly seems like the kind of man who would have appreciated the effort.

The 1920s were also the heyday of overwritten, “purple prose” sports writing, and John Kieran was one of its most famous figures. Kieran wrote for The New York Times sports section for almost thirty years, filling his sports columns with references to Latin, law, poetry, nature, and the works of William Shakespeare. In the hours before ball games, Kieran could be found visiting museums, zoos, parks and libraries, and he had a habit of writing his articles in advance of the actual games. Later in life he put his vast knowledge to the test as a panelist on NBC’s long-running radio quiz show“Information, Please!” While I can’t say that Kieran ever really conspired to fix a numbers game, he certainly seems like the kind of man who would have appreciated the effort.

One of Kieran’s favorite subjects had to have been Babe Herman and the “Daffiness Boys” of the Brooklyn Robins. Given their name as a tribute to popular Brooklyn manager Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson, the Robins were notorious for their on-field follies. No Robin was more “daffy” than Babe Herman, who routinely led the league in errors, put lit cigars in his pockets, twice stopped to watch a long home run while running the basepaths only to be passed by the hitter and called out, and who did indeed double into a double play. Said a teammate of Babe Herman, “He wore a glove for one reason: because it was a league custom.” Another called him “the Headless Horseman of Ebbets Field.” Despite-or perhaps because of-his zaniness on the field, Brooklyn fans loved Babe Herman. Years later during World War II when many of the younger players were called to military service, Herman was brought out of retirement to play for the Dodgers. He singled in his first at bat but tripped over first base and was almost thrown out. The Brooklyn fans gave him a standing ovation.

One of Kieran’s favorite subjects had to have been Babe Herman and the “Daffiness Boys” of the Brooklyn Robins. Given their name as a tribute to popular Brooklyn manager Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson, the Robins were notorious for their on-field follies. No Robin was more “daffy” than Babe Herman, who routinely led the league in errors, put lit cigars in his pockets, twice stopped to watch a long home run while running the basepaths only to be passed by the hitter and called out, and who did indeed double into a double play. Said a teammate of Babe Herman, “He wore a glove for one reason: because it was a league custom.” Another called him “the Headless Horseman of Ebbets Field.” Despite-or perhaps because of-his zaniness on the field, Brooklyn fans loved Babe Herman. Years later during World War II when many of the younger players were called to military service, Herman was brought out of retirement to play for the Dodgers. He singled in his first at bat but tripped over first base and was almost thrown out. The Brooklyn fans gave him a standing ovation.

Ebbets Field Specs

Ebbets Field – Preserving Brooklyn’s Lost Shrine

Walter O’Malley – The Official Web Site

Sixth Inning : Notes of a Star to Be

America was officially involved in World War II from 1941 to 1945. Millions of men were called on to leave their jobs and fight overseas, and women stepped in to take their place in factories, offices, and schools–and on the basepaths as well. The All-American Girls Softball League was founded in 1943 by Phillip Wrigley, owner of the Major League Chicago Cubs, who wanted a women’s league that would eventually play in Major League stadiums while the men’s teams were on the road. The league played a cross between softball and baseball until the end of the 1945 season, when the name was changed to The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, and overhand pitching and smaller ball sizes were adopted.

America was officially involved in World War II from 1941 to 1945. Millions of men were called on to leave their jobs and fight overseas, and women stepped in to take their place in factories, offices, and schools–and on the basepaths as well. The All-American Girls Softball League was founded in 1943 by Phillip Wrigley, owner of the Major League Chicago Cubs, who wanted a women’s league that would eventually play in Major League stadiums while the men’s teams were on the road. The league played a cross between softball and baseball until the end of the 1945 season, when the name was changed to The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, and overhand pitching and smaller ball sizes were adopted.

Women were selected for their abilities to run, throw, catch, hit, and slide, but they were also expected to be “feminine,” and had to attend evening charm school classes with beauty salon owner Helena Rubenstein, who later condensed her lessons into a handbook given to all AAGPBL rookies. The players were paid well by the day’s standards, making $45 to $85 a week and often out-earning family members who worked “real” jobs. Four cities near Chicago-Racine and Kenosha, Wisconsin, Rockford, Illinois, and South Bend, Indiana-were chosen to host teams, and almost 200,000 fans turned out during the first season to watch the women play ball.

New teams were added in the next few years, and though Wrigley’s dream of women playing to packed Major League stadiums never did happen, the league enjoyed great success in small Midwestern towns during and after the war. Attendance peaked in 1948 though, as the return of professional ballplayers from the war and the beginning of televised Major League games in the early 1950s gradually drew fans away. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League played its last skirted season in 1954.

All-American Girls Professional Baseball League – Official Site

Seventh Inning: Duck and Cover

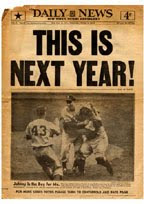

In 1955, the Brooklyn Dodgers won their first and only World Series championship, but by 1957 the end was near for the borough’s beloved bums.Jackie Robinson, who had broken baseball’s color barrier less than ten years ago and been such a brilliant and revered ballplayer, had already retired. Dodger fans were moving farther and father out Long Island, and there was nowhere for them to park their cars if they wanted to return for a game. Brooklyn owner Walter O’Malley began talks with the City of Los Angeles, and at the end of the 1957 season the Dodgers and their cross-town rivals the Giants moved to California.

In 1955, the Brooklyn Dodgers won their first and only World Series championship, but by 1957 the end was near for the borough’s beloved bums.Jackie Robinson, who had broken baseball’s color barrier less than ten years ago and been such a brilliant and revered ballplayer, had already retired. Dodger fans were moving farther and father out Long Island, and there was nowhere for them to park their cars if they wanted to return for a game. Brooklyn owner Walter O’Malley began talks with the City of Los Angeles, and at the end of the 1957 season the Dodgers and their cross-town rivals the Giants moved to California.

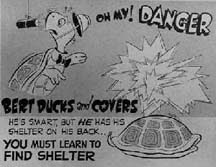

As devastating as the move was to fans in Brooklyn, there were far bigger things happening in the United States in 1957. In Little Rock, Arkansas, federal troops had to be called in to escort nine African-American students to Little Rock Central High School in what would later be seen as one of the most important events of the Civil Rights Movement. Tensions were also high in the “Cold War”between the United States and Russia, and the launch of Sputnik (Russian for “satellite”) caused a panic. The simple satellite spent three months in orbit and did nothing but transmit a beeping sound so that it could be tracked, but it fired the starting gun for the Space Race. American schools began to focus more on math and science, fallout shelters were dug in backyards, and nuclear bomb drills, introduced in the late 1940s when the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear device, became common again.

“Duck and Cover” was an educational film shown to American students. Years later, critics argued that ducking and covering would provide little real help in the event of a nuclear attack, and that the film did nothing more than heighten children’s fears. That didn’t stop the film from being shown over and over again to students from the late 1940s all the way, incredibly, to the 1980s. My father, a boy in the 1950s, remembers duck and cover drills in his own school.

“Duck and Cover” was an educational film shown to American students. Years later, critics argued that ducking and covering would provide little real help in the event of a nuclear attack, and that the film did nothing more than heighten children’s fears. That didn’t stop the film from being shown over and over again to students from the late 1940s all the way, incredibly, to the 1980s. My father, a boy in the 1950s, remembers duck and cover drills in his own school.

Watch Duck and Cover on YouTube

Hear a recording of Sputnik’s broadcast signal from space

Eight Inning: The Perfectionist

Kids have been playing Little League baseball since the league was officially founded in 1939, although not all youth baseball teams are official Little League programs. Rules vary from league to league, with some (like the Fulton Street Pawn and Loan team in this inning) playing a full nine innings, and others playing as few as six. The 1970s and 1980s saw the beginning of polyester uniforms and metal bats in youth baseball, and by this time millions of young people, both boys and girls, were playing organized ball.

As I write this, there have been only 17 official perfect games in the history of Major League Baseball. By comparison, more people have orbited the moon than thrown perfect games in the Majors, and no pitcher has ever thrown more than one. The most famous perfect game in Major League history has to be Yankee Don Larsen’s victory over the Brooklyn Dodgers in Game Five of the 1956 World Series, still the only perfect game (or no hitter, for that matter) in postseason history.

The ninth inning of Michael’s perfect game in my story is loosely based on the ninth inning of the perfect game thrown by Sandy Koufax of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1965. I’ve tried to evoke the poetry of Dodgers radio announcerVin Scully‘s call of that game, including a nod to my favorite line from that broadcast: “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world.”

The ninth inning of Michael’s perfect game in my story is loosely based on the ninth inning of the perfect game thrown by Sandy Koufax of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1965. I’ve tried to evoke the poetry of Dodgers radio announcerVin Scully‘s call of that game, including a nod to my favorite line from that broadcast: “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world.”

I was nine years old the year this story is set, and the 80s became the decade that shaped my young life. Though I know I’m not alone, films likeStar Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark had a profound impact on me as a boy, and I love including them here, if only in a small way. Michael and David in this inning are named for me and my brother John; Michael and David are our middle names.

Sandy Koufax’s Perfect Game

Vin Scully’s radio call of the ninth inning

Ninth Inning: Provenance

Five years after the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left for the West Coast, the New York Mets were added to Major League Baseball as an expansion team. Headquartered in Queens, the Mets never fully replaced the Dodgers in the hearts of Brooklyn fans, even though their team colors–blue and orange–were meant to pay tribute to Dodger blue and Giant orange. The Mets logo also incorporates buildings from the Brooklyn skyline as well the Brooklyn Bridge, which, like the team, was created to connect the boroughs.

Five years after the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left for the West Coast, the New York Mets were added to Major League Baseball as an expansion team. Headquartered in Queens, the Mets never fully replaced the Dodgers in the hearts of Brooklyn fans, even though their team colors–blue and orange–were meant to pay tribute to Dodger blue and Giant orange. The Mets logo also incorporates buildings from the Brooklyn skyline as well the Brooklyn Bridge, which, like the team, was created to connect the boroughs.

The expansion Mets were terrible in their early years, losing more games in their first season than any team since the 20-134Cleveland Spiders of 1899. To many abandoned Brooklyn fans, the awful Mets were like the return of Babe Herman and the Daffiness Boys, and support for New York’s “loveable losers” grew. Fans’ loyalty was rewarded when the “Miracle Mets” went from last place in 1968 to World Series champs in 1969 on the strength of young pitching talent like Cy Young Award Winner Tom Seaver, and the Mets enjoy continued popularity throughout the five boroughs to this day.

In 2006, a Babe Herman Pro Model Signature Bat was sold to a collector at auction for $1,508.00. Tobacco stains and cleat marks proved it had been used in games, but there is no way to know if it was the same bat Herman used to hit into the famous double/double play. Oddly, the bat does bear the remnants of three mailing stamps on the barrel, and faint, illegible writing that may be the address of Spalding, the bat’s manufacturer. How or why the bat was mailed back to the factory no one knows.